Few rifle-cartridge combinations carry the historical weight — or shoulder-bruising recoil — of the .45-70 Government cartridge and the Springfield Trapdoor rifle. Known for its unforgiving kick and rugged simplicity, this post-Civil War powerhouse earned a reputation that lingers like black powder smoke on a cold morning.

The .45-70 cartridge, paired with the Springfield Trapdoor rifle, remains large in the chronicles of American military history. They formed a solid pairing in postbellum and West-expanding America: a large black-powder cartridge and a rifle design which were able to endure the present hardships. Their U.S. adoption tells a story of technological inertia emanating from the American Civil War, of resource constraints in a bloodily reunited nation focused on rebuilding, and of a combined weapon that was, perhaps much like the United States itself at the time, not particularly refined but undeniably robust and imposing.

For roughly two decades, the .45-70 cartridge and the Springfield Trapdoor defined the small arms firepower of the U.S. Army. True, their adoption coincided with the tail end of the black-powder era as smokeless powder began casting its less smoky ominous shadow over military stockpiles around the world. Albeit for noted drawbacks and visible obsolescence even by 1870, the .45-70 and its Trapdoor companion easily earned a reputation that was undeniably American— with the cartridge’s sheer size, the rifle’s uncanny simple durability, and by its capability of lobbing a 405-grain bullet at targets like a rock from a hand catapult.

Postbellum Problems: Origins of the .45-70 Cartridge

The .45-70 Government cartridge can trace its birth to an era in American history dominated by post-Civil War reconstruction, industrial expansion, and the needs of an Army that, the primary national focus less than a decade earlier, was now immensely underfunded, and could not afford basics, let alone any form of cutting-edge firearms development program. The nation’s previous cartridge, the .50-70, had been introduced in 1866 with efforts to retrofit leftover Civil War arms to breech-loading designs such as the ever-improving Springfield 1866, M1868 and M1870. By mid-1870, the increasing improvements found necessary far exceeded retrofit capabilities and this weapon system was starting to resemble little more than wishful thinking, especially as European powers were steadily standardizing new weapons platforms with better ballistics.

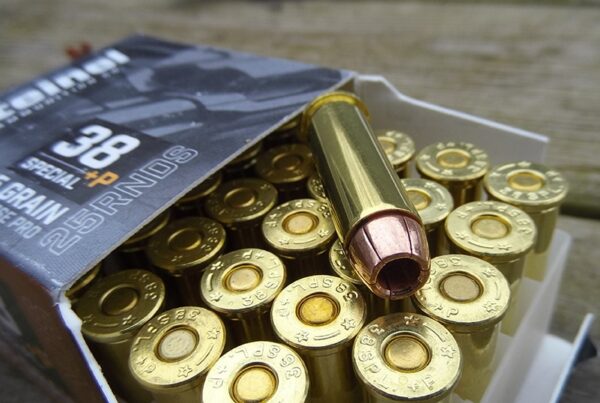

The .45-70 cartridge comprised a .45 caliber projectile crammed into a metallic case packed with 70 grains of black-powder. The bullet weighed 405 grains and packed devastating stopping power, hard-flung at a muzzle velocity of approximately 1,350 feet per second, a stark contrast to the higher-velocity small-caliber smokeless rounds that began appearing by the early 1890s.

Acknowledging the constraints of its development, the .45-70 was not only acceptable, it was a solid admission into the world of small arms. With a single round, the cartridge delivered man or beast-dropping terminal energy at short and medium ranges which exceeded the practical use of pistols and shotguns. Any detractors, reflecting on the cartridge’s ‘rainbow-like’ trajectory and received shoulder-kicking recoil, were still found admiring its sheer stopping-power.

The Springfield Model 1873: A Retrofit Rearmament

For nearly a decade, U.S. small arms engineers had been actively engaged in retrofitting the immense stockpile of Civil War small arms. The implementation of trapdoor breechblocks into these various muzzleloader designs incurred a vengeful cascade of increasing modifications needed so as to allow use of metallic cartridges. From the years of constant field testing and piles of retrofits, arose the Springfield Model 1873.

Adoption of the Springfield Trapdoor design, able to be produced en masse, paired with the hearty .45-70 Government, and robust enough to survive harsh treatment from those venturing into the Frontier, truly made sense. Furthermore, it allowed for some versatility, as the Army issued it in both a rifle and a carbine configuration for cavalry. The carbine version, being shorter in length at 22”, was intended to be complimented with a merely reduced powder 405 grain .45-55 cartridge of roughly 1,100 feet per second velocity.

The trapdoor mechanism presented itself as a defining feature, albeit both a positive and an equally negative one. Far superior to the previous muzzleloaders of file and rank infantry, this design greatly reduced the actions and the time required to be ready for firing. However, this did not remove the limitation of firing only single shots followed by pause between rounds for manual reloading. Where the Springfield Trapdoor fell flat (unlike its trajectory), was in usage against more mobile adversaries or those armed with more rapid-fire weaponry.

Smokeless-Powder and the Springfield’s Eventual Fade

Come the late 1880s, the writing on the wall for the pair was in large BOLD letters. The emergence of smokeless-powder cartridges and repeating arms forced a new age of smaller-caliber, higher-velocity projectiles and rifles which rendered the black-powder behemoths undeniably outclassed. There had been attempts to delay the technological tide. Although improvements had been regularly introduced even as late as February 1890 with the Model 1890, in December of 1890 the Ordinance Department formally convened a board determined to find replacements for both the cartridge and the Trapdoor. Ultimately, the Army adopted a new pair, the Krag-Jørgensen rifle and the .30-40 cartridge in 1892. This did not however signify the end of the Springfield Trapdoor’s U.S. military career, as it remained the predominantly carried arm even in 1898 a result of crawlingly slow replacement efforts.

However, the .45-70 cartridge was far from ever being abandoned. Though decidedly obsolete militarily, it was already a favorite of civilians hunting larger game. Its ballistics made it indispensable for taking down larger targets, and firearms manufacturers continued chambering a multitude of small arms platforms for the round. In fact, one of earliest American smokeless-powders introduced, Laflin & Rand Sharpshooter (1897), was designed specifically for use in the .45-70 Government cartridge and was able increase its original projectile velocity to 1,730 feet per second in a 26-inch barrel.

Closing the Breech: The Springfield’s Final Chapter

The partnership of the .45-70 Government cartridge and the Springfield Trapdoor may not have been at the forefront of cutting-edge weaponry when first introduced, but was most certainly tough, reliable, and supremely capable of delivering a brute force to reckoned.

About the author:

Zahari Stolley is an apolaustic military historian, haphazard amasser of antiquarian books, and a relatively ambivalent connoisseur of firearms who has spent far too much time amongst the dust of bookshelves and the lead of battlefields. Educated in medicine and harm dealing by numerous conflicts, he often loses track of whether he was primarily treating casualties or dodging bullets. When not attempting friendship with uninterested wildlife, he is likely either mispronouncing obscure terminology or floundering at the prospect of his library ever being functionally organized.

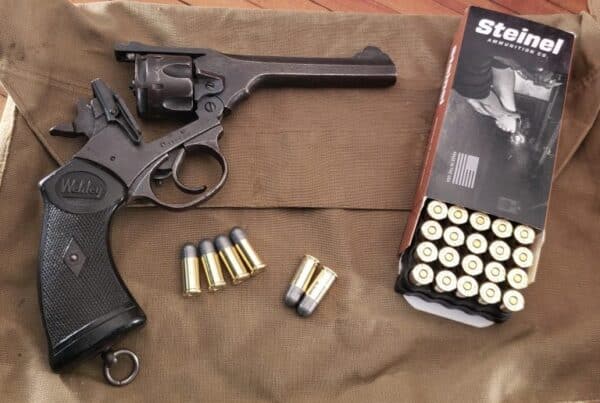

Photography by Oleg Volk

Is there more places that sell 45-70 trapdoor safe ammo, other than Stei

Inal ammo??

They’re out there. You can use your favorite search engine and roll the dice 🙂

Fantastic article; thanks for taking the time. You failed to mention Steinel 45-70 so I will. Steinel produces the most consistent 45-70 ammo I’ve shot and is my “go to” brand for that caliber. Wish I would have found you sooner. Thanks.

Thanks, Steve! We really appreciate the sentiment.

Worth reading for the historical information.

03 Springfield , I may be wrong. Although I’ve read that the USA did not have nearly enough M1 Garands to issue to the 78,000 regular US Army troops in 1941. Also I have read very few soldiers in the Pacific region including the Philippines and Gaum had Garands. I believe the Philippine Army had M1917 Enfield rifles from WW1.

Extremely well written and interesting. Thank you